When you hear ADHD, you probably think of fidget spinners, colorful planners, and productivity hacks. But long before social media started talking about it, ADHD had a fascinating and sometimes controversial journey to becoming the diagnosis we know today. Let's time-travel through the history of ADHD, from 18th-century observations to modern-day neuroscience.

In ancient Greece, Hippocrates described people whose minds "would not remain still," who shifted thoughts quickly, and needed constant movement, traits we might now associate with ADHD. He attributed it to excess of fire element in their bodies [1].

Way before TikTok and Zoom meetings tested our attention spans, Scottish physician Sir Alexander Crichton described people with "mental restlessness." They couldn't stick with tasks, lost focus easily, and felt constantly distracted [2].

British pediatrician Sir George Still presented a series of lectures describing children who had difficulty controlling their behavior, even with proper discipline. He believed it wasn't about parenting, it was something innate. Unfortunately, he called it a moral defect (those were Victorian times so why not!).

By mid-century, doctors thought these symptoms came from mild brain injuries, calling it "Minimal Brain Dysfunction." That theory didn't stick (for good). In the 1960s, the term "Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood" appeared in the DSM-II (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), marking one of the first formal psychiatric classifications for what would later become ADHD.

Note that DSM, which will be mentioned in this blog more than once, is a diagnostic bible for psychologists and psychiatrists, it prescribes the rules for diagnosis.

As research advanced, experts realized that inattention was just as important as hyperactivity. The 1980 release of the DSM-III introduced "Attention Deficit Disorder" (ADD), with or without hyperactivity. This was a major shift acknowledging that inattentiveness could exist even in those who weren't overly active. Ritalin use became widespread for children with hyperactive behaviors.

In the DSM-III-R, the term "Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder" was adopted, uniting the inattentive and hyperactive features under one name.

The DSM-IV introduced three presentations, namely inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive, and combined type.

The DSM-5 recognized that ADHD isn't just a childhood thing, it can last well into adulthood, affecting work, relationships, and daily life [3].

The DSM-5-TR kept the core ADHD diagnostic criteria the same but refined the language for greater clarity, removed outdated terminology, and integrated the latest research insights on how ADHD presents and impacts adults.

From moral judgment to brain science, ADHD's history shows just how far our understanding of mental health has come. Today, we're fortunate to live in an era where ADHD is seen through the lens of neuroscience and compassion, not dismissed as a moral defect or blamed on supposed brain damage.

So the next time someone says ADHD is "new" or "just an excuse," tell them it's been around for centuries. The only thing that's changed is that we finally know what we're talking about.

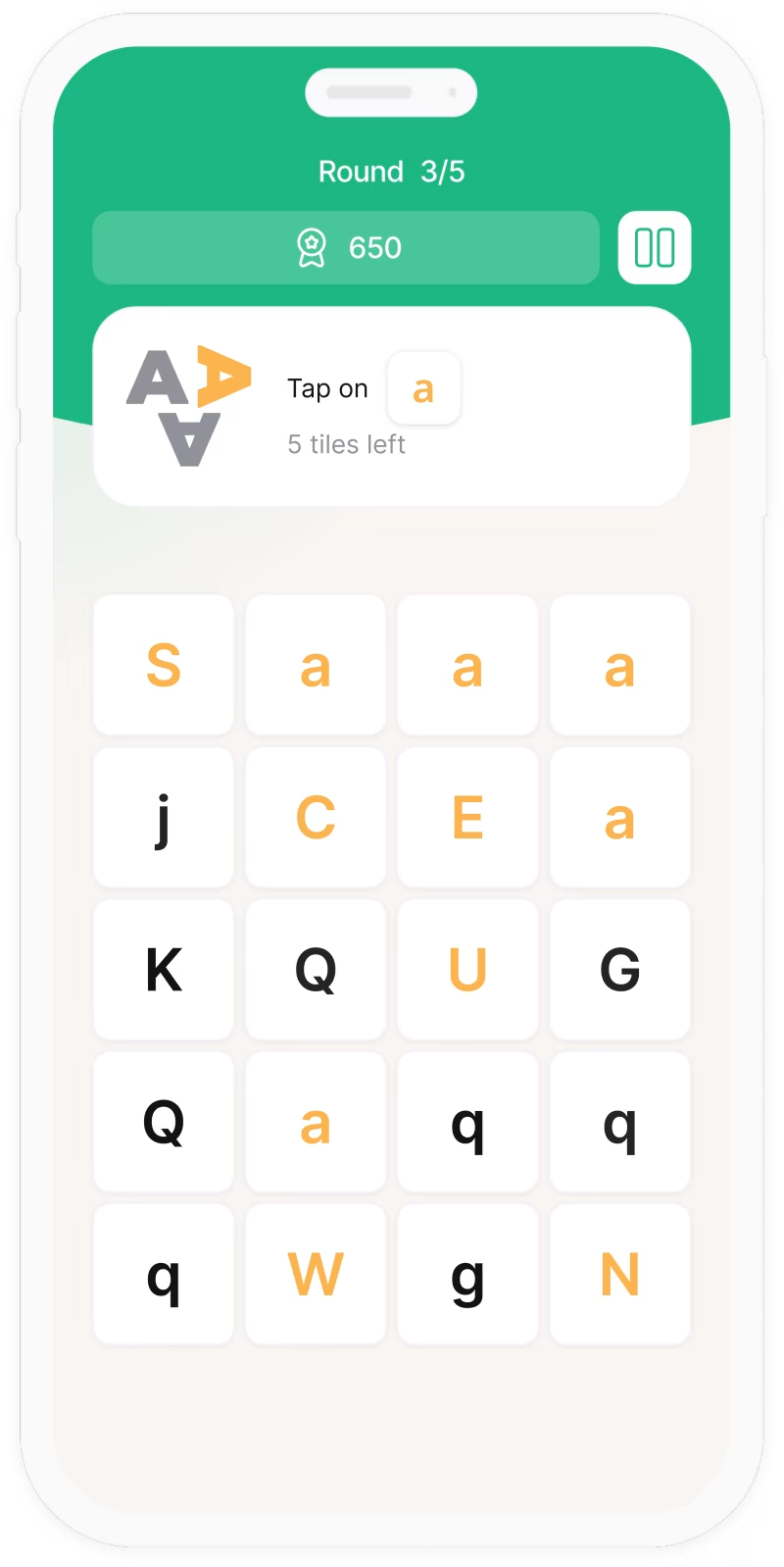

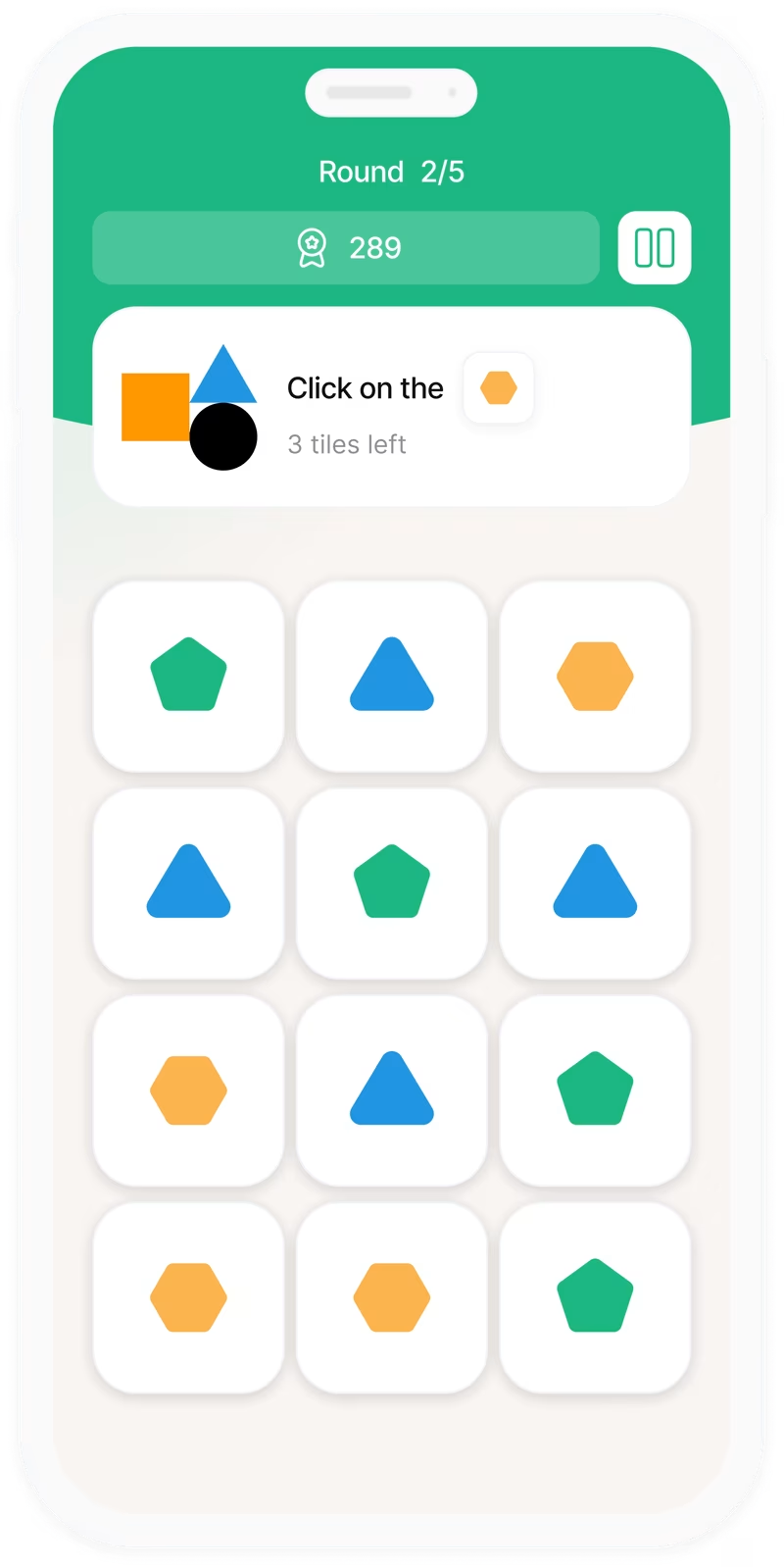

Whether you're here to focus better, calm your mind, or just feel a little more in control, we’re here to support you. One game at a time.